Considerations As The 2022 Corn Crop Approaches Maturity

EMERSON NAFZIGER

URBANA, ILLINOIS

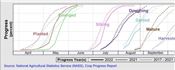

The 2022 Illinois corn crop was planted about two weeks later than normal, but slightly above-normal temperatures this summer have helped move crop development along (Figure 1); the crop is only a few days behind normal as it reaches late grainfilling stages and maturity.

With the forecast for warm weather to continue into September, we can expect the majority of the crop to reach maturity by mid-September.

One helpful tool to help track development and maturity in corn is the corn GDD tool located at https://mygeohub.org/groups/u2u/purdue_gdd.

There you can click on any county in the Midwest, enter a planting date and hybrid maturity, and get output that shows growing degree-day accumulation for this year compared to normal, along with predicted silking and maturity dates. A 110-day RM hybrid planted in Champaign County on May 10, 2022, is predicted to reach black layer on September 4. If it was planted on or before May 1, that hybrid should be mature now.

Crop condition and potential

The big story of the 2022 growing season in Illinois has been dry weather and related crop stress symptoms at times in some parts of the state. Some of this continues – the US Drought Map released today (September 1) still has 5 percent of Illinois in moderate drought and 17 percent as abnormally dry. The driest areas are in east central Illinois, including Champaign County and parts of nearby counties, and in west central Illinois, mostly in Hancock County and small parts of adjoining counties. These areas, especially in east central Illinois, have been in some stage of dryness or drought most of the summer. Rainfall has been higher than ideal in a few places in Illinois. But overall, corn yield prospects have not decreased much as the result of unfavorable weather in Illinois, and the August 1 estimate for Illinois corn yield is 203 bushels per acre, up one bushel from 2021. The crop condition rating has been around 70 percent good+excellent since pollination, which is similar to the rating in recent years except for 2019, when it was less than 50 percent most of the season after very late planting. Many people in drier areas have noted “tip-back” with kernels not developing on some length of cob at the ear tip. That is partly offset by good ear counts, and by the fact that canopies have remained intact with good color in most fields, so kernels should reach at least normal size. In fields with fewer than 450-500 kernels per ear but with the canopy in good shape up to maturity, kernels may get a little larger than normal, which will help yields.

There has been some talk recently that yields this year might be lowered as the result of below-normal sunlight amounts. Low sunlight has often been used to explain lower-than expected yields, presumably because low sunlight, like low rainfall, is a natural occurrence and not one for which humans can be held responsible. Sunlight is the energy source for all plant growth. But plants need water to utilize sunlight energy, and in Illinois, water mostly falls from clouds, and clouds lower the amount of sunlight. That makes for poor correlation between sunlight amount and corn yield: even without the 2012 season, when sunlight was high and yield low, this correlation is not high.

Total sunlight from June through August in Illinois this year was a little below normal, but in Champaign County, it was slightly higher than in 2021, when the county yield was record-high at 222.4 bushels per acre. Sunlight in Sangamon County this year was almost identical to that in Champaign County, but with better rainfall in Sangamon County, yields will likely be higher there. It seems that the supply of water is much more likely to influence yield than the supply of sunlight.

Nitrogen status and response

With stretches of dryness during the season and, in most places, no standing water since planting, it is likely that less N has been lost from Illinois soils this year than in any season since 2012. As soils dried in the weeks following planting, roots grew deeper, and aided by good soil aeration, plants were able to take up N with few problems.

Where soils dried enough for plants to show drought symptoms, their ability to take up both water and N dropped. Once some rain fell, water and N uptake increased, and canopy color was restored along with crop growth. Symptoms of N deficiency, even in plots where no fertilizer N had been applied, were slow to develop as mineralization provided N for early growth. Where N fertilizer was applied in a way that allowed roots to reach it early, canopy color was mostly good.

With a good supply of mineralized N and little N loss, we do not expect N availability to be a yield-limiting factor in most fields in 2022. Under such conditions, research tells us that yields should reach a maximum at modest N rates in trials this year, regardless of yield level. In fields where water was limiting at times through the middle part of the season, N response may depend on timing of water deficits. If water is adequate in mid-vegetative stages but declines going into pollination, low to modest N rates may maximize (lower) yields. When water limitations persist from mid-vegetative stages through pollination, it may take relatively high rates of N to produce relatively low yields. We believe the former results from having normal kernel number that the plant is unable to fill completely; while the latter is due to limitations on the number of kernels formed.

One lesson to take from an “N-abundant” but occasionally dry season like 2022 is how N placement and timing can affect plant access to N.

Sidedressed N, especially UAN dribbled on the soil surface, usually remains unavailable to the plant as long as there is little or no rainfall to move it into the soil. Unless the rain never arrives, that may not be a problem if enough N (one-third to one-half of the total) is applied at or near the time of planting, placed to allow developing roots to have access to the N. But where little N was applied early, or where early-applied N is not available to young plants, surface- applied N may be unable to relieve deficiency as long as the soil stays dry after application. That can result in yield loss, especially if deficiency persists to mid-vegetative stages. The longer UAN or urea remains on the surface, the more N loss from volatilization is likely to take place, even if a urease inhibitor was used.

Where high rates of N were used in areas that have remained dry most of the season, there is a good chance that more N than usual is present in the soil as the crop matures. Some of this is likely to leach to tile lines and to leave the field by next spring. A grass cover crop would take some of this up and lower the amount that leaves the field.

Standability

There is often some concern as maturity approaches that stalks may not remain intact and standing up to harvest. That’s especially the case when conditions like drought and foliar diseases limit the ability of the plant to maintain photosynthesis to keep sugars in the stalk (to keep the stalk alive) until maturity. The 2022 season, by most accounts, has been one with little foliar disease. We don’t know if that lowered the amount of fungicide applied, but it did help to maintain canopy color and photosynthetic rates through grainfilling.

The lack of extended wet periods has also helped roots to remain intact and healthy, which helps keep leaves and stalks intact as well.

In Champaign County where conditions were very dry through June into July as stalks were elongating, stalks tend to be small in diameter, but to have good resistance to breakage. This is due in part to lignin production and deposition into stalk rinds. With strong stalks, roots firmly embedded in the soil, and ears of only modest size, the crop should be in good shape to remain standing in the field until it reaches the grain moisture at which harvest begins. There may be exceptions to this in places, but as is usually the case, if there are no windstorms over the next few months, lodging should not be a problem.

Drydown and harvest

When the corn crop reaches black layer (maturity) during warm weather in early September, it usually dries down quickly, starting from 30 to 32 percent moisture at black layer. That’s especially true when the crop matures and begins to dry without a lot of disease or extended periods of wet weather, as it’s doing this year. Husks appear to be drying down while there is still some green leaf area, and when that’s the case, we expect husks to begin to loosen quickly. Once they are loose to allow air to circulate around the kernels, drying will speed up. The fastest drying we have measured under warm temperatures in early September is about 1 percentage point of moisture per day. That’s probably close to the maximum for grain drying rate in the field, but as long as days are warm and breezy, using this rate to track drying progress can help avoid letting grain get below 20 percent moisture before we realize it.

One recurring issue when the crop matures early and dries down quickly is the increase in harvest loss as grain moisture drops below 16 or 17 percent. Most such loss occurs when ears hit the stripper plates as stalks are pulled into the corn head, with kernels loosened on impact and thrown out onto the ground. There are devices designed to capture such kernels before they escape, but harvesting at higher moisture is likely more effective. It’s a tradeoff, of course, between paying more for drying or losing more kernels. Combine adjustments can help, but may not solve the problem if grain moisture drops to below 16 percent. We have all seen fields with great stands of volunteer corn (2 kernels per square foot is about one bushel per acre) following a rain after harvest, and hope we can avoid that in 2022. ∆

DR. EMERSON NAFZIGER: Research Education Center Coordinator, Professor, University of Illinois

Figure 1. Developmental progress of the 2022 Illinois corn crop, compared to 2021 and the average of the past five years.