|

Replanting Corn And Soybeans

DR. EMERSON NAFZIGER

URBANA, ILL.

Both corn and soybean planting progressed at about normal speed into May, with 56 percent of the Illinois corn crop and 31 percent of the Illinois soybean crop planted by May 3. Unfortunately, the period of warmer, drier weather we have been hoping for has not yet materialized.

Over the ten days through May 5, about two-thirds of Illinois has gotten from 3 to more than 6 inches of rainfall. Temperatures have not cooperated very well, either. Although there have been a few warm days, only about 160 growing degree days have accumulated here in Champaign since April 9, and we’re predicted to get only about 35 GDDs over the next week, with a chance of frost on May 9.

Corn requires about 115 GDDs from planting to emergence, so corn planted before April 21 should be emerging this week. Eight percent of corn and two percent of soybeans were planted by April 19, and those same percentages had emerged by May 3. If a field was planted more than 120 GDDs ago and plants don’t seem to be emerging, dig up some seeds and see if they’re close to emerging, or if they might have stopped developing at some point. Seeds that have spent time under water or in saturated soils may be at risk. Cool soils may have prolonged their life long enough so they’ll struggle up eventually, but such fields may not be very pretty.

It’s unlikely, but not impossible, that frost later this week might be severe enough to kill emerged plants. The growing point of corn is protected in the soil, and few fields have made enough growth to be damaged much by light frost. Wet soils cool more slowly than dry soils, so offer a little better protection. Dark-colored soils also radiate better, and so offer more protection from radiational cooling that can kill leaf area that’s exposed to the sky (that is, more horizontal) on a clear night. In a planting date study at Urbana in 2005, corn planted on March 30 was at the 2-leaf stage when the low temperatures dropped to 32 degrees or less (the lowest was 28) for four nights in a row the first week of May. A substantial number of plants were killed (on a more or less random pattern down the row), but enough survived to compare yields from that and later plantings at 30,000 plants per acre. It was a very dry year with low yields, but the same population planted on April 19 yielded 115 bushels per acre compared to only 47 bushels from the March 30 planting. So we’ll only know the real effects after the period of low temperatures, and maybe not until the end of the season.

Soybeans are vulnerable to frost injury for only a day or so as they’re coming through the soil. Wet soil holds heat better and also cracks open less during soybean emergence, which lessens the chance of damage. Cool, wet soils are a bigger problem for both crops than a night of light frost.

If more than 140 or GGDs have accumulated since planting, it’s time to evaluate the stand and to decide if it warrants replanting. Hardly ever are stands decreased uniformly over an entire field, so while it’s helpful to count stands in several places across the field, it’s also necessary to get an idea of how much of the field consists of patches with no plants at all. A drone may be helpful in doing this. If the stand is good in places and missing in other places, calculating a (weighted) average stand doesn’t help, other than to suggest how much of the field might need to be planted again.

Corn replanting

Back in the 2000s we generated data to update a replant decision tool for corn, by planting at different dates and establishing a range of plant populations within each planting. That tool is available in the Illinois Agronomy Handbook. But I do not believe that the data used to produce that tool is valid for current hybrids, which lose yield more slowly as planting is delayed, and that also show less yield loss as plant population decreases in comparison to earlier hybrids.

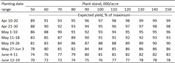

We found little interaction between planting date and plant population in the earlier sets of data used to formulate replant guidelines: that is, population responses didn’t change much as planting date changed. We think that’s still the case, which means that we can combine planting date and plant population data from different trials without producing big inaccuracies. Based on that, I used our most recent planting date and plant population response data to generate Table 1.

If lower stands are mostly from random skips down the row rather than from larger spots without plants, use the table above to help decide whether or not replanting will pay for itself. Use the original planting date and existing stand to estimate expected percentage of maximum yield, then move to a later planting date range and expected plant stand from replanting to determine expected yield if the field is replanted. As an example, if a field planted on April 15 has a stand of 26,000, we would expect it to yield 92 percent of maximum. If we can replant on May 15 at 35,000 plants, we would expect 95 percent of maximum yield, for an increase of 3 percent, or 6 bushels if we expect the field to yield 200 bushels per acre. Note also that unless replanting can be done (in this case) before the last week of May, there’s little chance that replanting will result in more yield than keeping the current stand.

Depending on replanting costs, it might or might not make sense to replant for 6 bushels per acre; this is where judgement comes into play. If the stand that’s there is uneven and it looks like some plants might not survive to thrive, or if there are many spots (more than one row wide) without any plants, then it’s entirely possible that the original stand will yield less than 92 percent. Crop insurance and seed company policy on replant seed also come into play. And some prefer to replant “ratty-looking” fields just because they don’t want to look at them all season and wonder if they should have replanted. Keep in mind that replanted corn will usually have higher grain moisture at harvest, which should be counted in the replant cost.

Are there any adjustments we should make if we decide to replant? If all of the N has been applied, the replanted crop may not need any more, given that we haven’t had warm soils that enhance losses. But where there’s been a lot of rain since N was applied, nitrate-N has been moved down into the soil, and it might pay to apply some N with the planter to make sure there is some there after the crop emerges, especially if soils are still cool (meaning low rates of mineralization) at the time of replanting. There’s no reason to change plant population or hybrid maturity from what was planted originally, although actual hybrid may have to change depending on seed supplies.

It can be difficult and frustrating to “repair-plant” partial stands, but if nearly all the missing plants are in spots rather than scattered down each row, and you can find a 4- or 6-row planter to minimize the area that ends up with twice too many plants, that can save costs. In any corn replanting operation, leaving existing plants to grow along with the plants from replanting is often disastrous: hybrids tolerate high populations, but not double what they should be. Using trash movers to dislodge existing plants might work OK in some cases. But in many cases, especially for whole fields, existing plants should be sprayed out with herbicide so they don’t compete with later-planted plants.

Replanting soybean

Evaluating soybeans stands is a little more “complicated” than evaluating corn stands, although the same problem of uniformity of (remaining) stand occurs in both crops. It does make it easier when conditions are such that few soybean plants emerge, and given that we consider 80 percent stand establishment to be acceptable in soybean, we expect, and more often see, stand reductions in soybean that are more uniform than those we see with corn. An adage that we might apply to soybean is, “When plants are easy to count without bending over, there aren’t enough of them.”

One concern is that those who advocate for lower seeding rates and early planting may encourage stands to be kept even when they will result in a yield loss. We have over the years learned that stands that may look inadequate when plants are small usually fill in nicely and produce high yields. This has taught us to be patient when growth starts slow and not to let emotions guide replant decisions. Still, staying with stands that are too low to produce maximum yields should not be done just to “prove a point.”

Instead of laboriously counting the number of plants in a hoop or 3 ft of row, it might be faster and accurate enough to use a scale of 0 to 4, with each number the approximate number of plants per square foot. On this scale: 1 (43,560 plants per acre) would be too low; 2 (about 87K/acre) would be probably be acceptable if plants are healthy; 3 (131K) is a full stand; and 4 (174K) is more than enough. One plant per square foot is a plant every 4.8 inches in 30-inch rows, and every 9.6 inches in 15-inch rows. With a little practice, it should be possible to get close-enough stand counts with a relatively quick glance at the ground. Getting quick counts in more places is usually preferable to getting counts that are more accurate in fewer spots.

I took the same approach to estimating expected outcomes from replanting soybeans (Table 2) as I described above for corn. One caveat is that we do not have much data from recent studies that included both planting date and seeding rate, so our assumption that soybeans respond similarly (on a percentage basis) to seeding rate at different planting dates is not well supported. Joshua Vonk did some studies that included both seeding rate and planting date in 2010 and 2011 and found no interaction between these two factors across sites. But as others have found, he didn’t see much response to seeding rate, so not finding such an interaction was expected. Those studies also didn’t include planting quite as early or quite as late as the table includes, and so the indication that 50,000 plants will yield only 10 percent less than 130,000 plants when planted in mid-June isn’t rock solid.

According to Table 2, as much yield will be lost from planting after May 20 as from losing nearly half the stand from April-planted soybeans. Experience and judgement will play a role in this decision, as will the cost of replant seed and planting. Unlike corn, there’s no need to destroy existing soybean plants when replanting. In a study we did some years ago, supplementing low plant stands with a reduced amount of seed or destroying the low stand and planting a full rate of seed produced the same yield. ∆

DR. EMERSON NAFZIGER: Research Education Center Coordinator, Professor, University of Illinois

Table 1. Corn yields (percent of maximum) for different combinations of planting

date and plant population. Derived from the results of 39 planting date

and 44 plant population trials in Illinois.

Table 2. Soybean yields (percent of maximum) for different combinations Table 2. Soybean yields (percent of maximum) for different combinations

of planting date and plant population. Derived from the results

of 29 planting date and 25 seeding rate trials in Illinois.

|

|